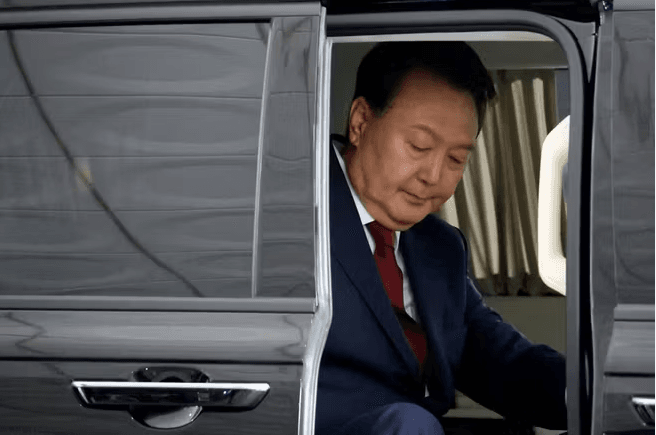

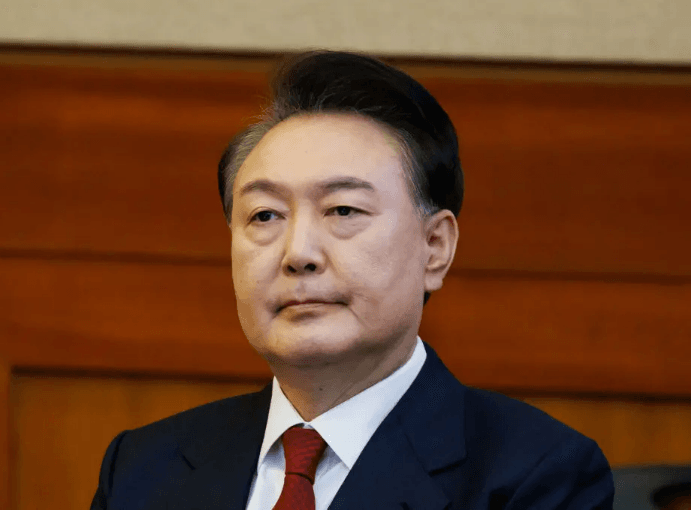

A South Korean court has sentenced former president Yoon Suk Yeol to life in prison after finding him guilty of leading an insurrection linked to his controversial declaration of martial law in 2024. The landmark ruling marks one of the most dramatic political downfalls in modern South Korea, a country long viewed as a model of democratic stability in the region. Delivering the judgment at the Seoul Central District Court, presiding judge Ji Gwi-yeon ruled that Yoon’s actions were aimed at crippling the legislature and suppressing political opposition. According to the court, the former president ordered troops to move toward the National Assembly during the crisis, an act prosecutors argued was intended to obstruct lawmakers who had blocked his policy agenda. The court also noted Yoon had shown little remorse for his actions.

From Martial Law to Impeachment

Yoon shocked the nation in December 2024 when he appeared in a late-night televised address announcing emergency military rule. He justified the decision by citing alleged threats from “anti-state forces” and claims of opposition interference in governance. Civilian rule, however, lasted only six hours after lawmakers forced their way into parliament and voted to overturn the order. The episode triggered mass protests, rattled financial markets, and alarmed international allies including the United States.

Heavy Sentences for Key Allies

The court also handed lengthy prison terms to senior officials linked to the crisis. Former defence minister Kim Yong-hyun was sentenced to 30 years in jail for his role in facilitating the martial law operation. Prosecutors had pushed for the death penalty against Yoon, the maximum punishment under South Korean law for insurrection. However, the country has maintained an unofficial moratorium on executions since 1997, making life imprisonment the harshest enforceable sentence in practice.

Supporters Rally Outside Court

Thousands of Yoon’s supporters gathered outside the courthouse ahead of the verdict, waving placards and chanting slogans in his defense. Police deployed heavily around the court complex, forming barricades with buses and officers in riot gear to prevent unrest as the judgment was delivered.

Echoes of a Troubled Past

Analysts say the failed power grab revived painful memories of the military coups that shaped South Korea’s political landscape between the 1960s and 1980s. Yoon, who has been held in solitary confinement during multiple trials, has repeatedly denied wrongdoing. He maintains that his declaration of martial law was meant to protect constitutional order and counter what he described as an opposition-driven “legislative dictatorship.” Prosecutors, however, framed his actions as a calculated attempt to consolidate power and extend his rule.

In a separate case earlier this year, former first lady Kim Keon Hee received a 20-month prison sentence over bribery allegations unrelated to the martial law crisis.

Conclusion

The life sentence against Yoon Suk Yeol closes a tumultuous chapter in South Korea’s political history. The ruling reinforces judicial independence and underscores the constitutional limits of executive power, even at the highest level of government. As the country reflects on the crisis, attention now turns to institutional reforms and safeguards aimed at preventing similar constitutional confrontations in the future.